Everything in Its Place

Even if you’ve only logged a few hours as a student, you’ve probably heard the adage that “a good landing begins with a good approach.” On downwind, if you’re on speed, with the power set and the airplane configured for landing, the odds of making a smooth touchdown on target increase substantially.

Too often, however, we don’t apply a similar principle to takeoffs. Sure, we follow checklists to start the engine and complete the run-up. Yet frequently we launch into the sky without having completely prepared the cockpit– especially the avionics (and nowadays our electronic flight bags)–for what’s about to happen next.

French chefs have a motto: mis en place, “everything in its place.” The idea is to collect, prepare, and organize all ingredients for a meal before you light the fire or add even the first cup of diced onions to the pan.

By the time we start cross-country training, we’re familiar with the process of planning a flight, including:

- Laying out a route

- Estimating fuel requirements

- Calculating weight and balance and performance

- Completing a navigation log

- Obtaining a preflight briefing

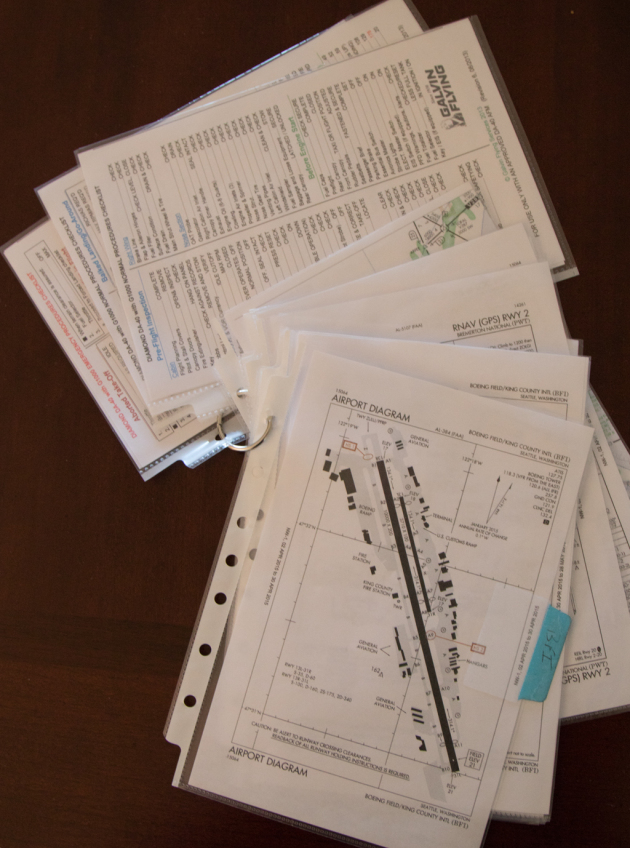

In the rush to get started after we preflight the airplane, however, we don’t spend enough time preparing the cockpit, a task that ironically has become more challenging with the widespread adoption of tablets and apps like ForeFlight and Garmin Pilot. We no longer have to sort and organize stacks of charts, Chart Supplements, printouts of weather reports, and navlogs, but we still have to make sure that we have obtained all of the relevant, current information for a flight and that we have a system for organizing and accessing critical details in the cockpit.

For example, it’s especially easy for IFR pilots to get lazy about checking and arranging charts for departure procedures and approaches. The tedious process of revising Jeppesen binders is now an automated update that happens invisibly in the background. It’s easy to miss important changes to procedures, and you must allow time during your planning and preflight activities to review and organize the charts you expect to need.

For example, it’s especially easy for IFR pilots to get lazy about checking and arranging charts for departure procedures and approaches. The tedious process of revising Jeppesen binders is now an automated update that happens invisibly in the background. It’s easy to miss important changes to procedures, and you must allow time during your planning and preflight activities to review and organize the charts you expect to need.

Apps like ForeFlight include a binder feature (video here) to help you collect a set of charts in a logical sequence for your departure, enroute alternatives, arrival, approach at your intended destination, and alternate(s). You can also use the annotation feature (video here) to mark up and highlight important details on those charts. (Another example of marking up an approach cart is at my blog, here.)

Even if you only fly VFR, you can use those features to review and organize airport diagrams and related information before you set out on a trip.

The steps above help you take care of the paperwork (real or virtual) for a flight. But before you start the engine, like a professional chef, take a moment to carefully and critically examine the cockpit. Are all items you’ll need for the flight logically organized, secure, but also easily accessible? Today, in addition to our tablets, we fly with charging cables, backup batteries, mobile phones (as backups to the tablet), and a host of other gizmos and accessories that didn’t exist even a decade ago. But those wonderful devices aren’t useful buried in a bag in the back seat, and they can become a hazard if they tangle with controls or distract you.

Later, after you complete the runup and before takeoff checklists, ensure that your workspace—the  cockpit—is ready for departure.

cockpit—is ready for departure.

Use your finger to trace a path down the avionics stack or through the frequency and CDI displays on a PFD and MFD. Is each active and standby communication and navigation frequency set to something useful? Is the GPS set up with a flight plan, or at least the destination or a nearby airport as a fix? Even if you’re making just a quick hop to a familiar airport restaurant, loading the AWOS/ATIS and CTAF/TWR frequencies for your destination before you take off means you have less to look up or fiddle with after you take off. Putting the destination airport “in the box” means you have a reference ready when you call the tower or make position reports on the CTAF.

Finally, take another moment to deliberately check, touch, and verbalize the position of switches and critical controls such as the fuel tank selector, flaps, trim, interior and exterior lights, and pitot heat.

That pause is a final confirmation that you didn’t miss an important item if your checklist was interrupted by ATC or another distraction. And you’ll be more confident that you’re ready to cook.

By Bruce Williams, CFI, CFII